The total eclipse of the

Sun

is an astronomical phenomenon of extraordinary beauty

which will excite every nature lover. Most of these beautiful phenomena will

happen unnoticed by the media and the general public. The

total solar eclipse of August 11, 1999

was, however, quite exceptional. The reason for this was that the narrow

path of totality where the total solar eclipse was

visible passed through densely populated areas of Europe and only just missed

the Czech Republic. The belt, which was about 120 km wide, passed through

England,

France,

Germany, Austria,

Hungary,

Romania and Bulgaria.

It then crossed the Black sea and continued through

Turkey,

Iraq and

the Middle East countries to

Asia.

Shortly before sunset the lunar shadow quickly made a passage through India and

the eclipse ended at sunset in the Bay of Bengal. As the total solar eclipse

occurs at the same place on the Earth roughly about once in 350 years the enormous

interest aroused by the eclipse of August 11, 1999 was understandable. However,

many people had to set off on a long journey without being certain of finding the right

place for observing this rare phenomenon whose maximum duration was a mere 143

seconds. Just one of the clouds, so much a part of the European sky, would be

enough to mar all efforts.

My journey to the eclipse began in 1962. It was back then when I learned at the

observatory in Brno that in 1999 there would be a total eclipse of the Sun in

Austria. Since then I had been thinking about the event. It was also on my mind

in the summer of 1971 in Jerewan when I was buying an

MTO lens for a reflex camera with a focal length

of 1.1 m. For a long time I had been worrying how I would get to Austria when we were

not allowed to travel there ...

Fortunately, this problem was nothing to be worried about in 1999, although

other worries took their place, such as the European weather itself which is not

the best for observing a phenomenon that lasts but a couple of minutes. The

ubiquitous clouds negotiating the ranges of the Alps make choosing an

observation place in Europe a nightmare even for the hardy. To top this Mother

Nature decided to play some practical jokes with us and replaced the mostly nice

weather, that had settled down for a relatively long period before the eclipse,

by two cold fronts driven across the Alps right at the time of the eclipse.

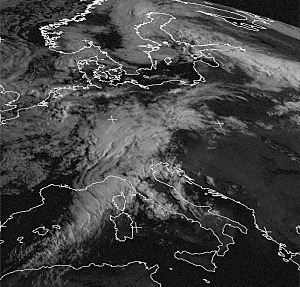

The morning of August 10, 1999 found me sitting at my computer pouring over

the recent images from a meteorological

satellite and the weather forecast

downloaded via the Internet from the server of Meteo France. The situation

looked exceptionally bad. The only ray of hope was a small hole

in the cloudy blanket over Hungary, between the Balaton lake and Szeged, visible

in Meteo France's weather forecast. I wanted to check whether other meteorological

institutions were of the same opinion, but they were playing it safe, probably

from fear of risking being blamed by disappointed people, and issued statements

of the "If it does not rain, you will not get wet" variety. There was nothing

left for it but to believe the French. At high noon the final decision was made.

We were going to Hungary, to the vicinity of the town of Paks, which should lie

in between the two cold fronts.

At 14.30 hrs our 8 member strong expedition sets off in two cars from the

Brno observatory. We consistently avoid all motorways, first class state roads

and main border crossings. We are scared of becoming stuck in the predicted

traffic jams. As we are crossing the border from the Czech republic to Austria

in Potorná light drizzle

gradually turns into torrential rain. The falling rain dampened our spirits in

direct proportion to the amount of water falling from the heaven. When we

finally weave our way, at about an hour till midnight, to the Balaton lake the

weather is beginning to improve. We drive around the hopelessly overcrowded

Balaton lake and head farther southeast. At midnight we are almost there. Just

a couple of kilometres from the centre of the totality belt we stop in a woods

where we are going to rough it until the morning. When we lie down on our

carimats, attended by hosts of mosquitoes, we have above us the canopy of the

sky with "millions" of stars and we are overwhelmed by the view of the Milky Way.

The mood is on the rise.

The buzzing of mosquitoes is not the best of lullabies, especially if you

have blood group B. I don't know why the beasts are not attracted by group O.

However, in the end fatigue takes over. The next thing I know I start awake as

light flashes and distant thunder sounds overhead. Before my sleepy head

registers what's going on heavy drops of water fall on the sleeping bag.

Goddamit, the cold front has arrived! But is this the first one or the second

one or ... I wish I could get online on the Internet and download a recent image

from the satellite. We have to seek shelter in the car and catch some sleep

sitting inside and waiting till the morning. Low spirits reach new depths.

However, after eight in the morning a strip of blue sky appears in the west and

extends, slowly but definitely towards us. The front has gone and everyone

cheers up.

Morning lethargy quickly disappears as we get into the cars and drive the

remaining few kilometres to our target looking for a spot suitable for

observation. We find it on the edge of a typical Hungarian field of maize about

2km SSE from the village of Németkér. It is

almost at the centre line of the strip of totality, less than ten kilometres

away from the town of Paks. The weather

looks splendid. The sky is clear with the final traces of the disappearing

front discernible at the distance in the east. How I wish the eclipse happened now!

But right now, the total eclipse is almost minus three hours away. About an hour

later small, under normal circumstances beautiful, cumulus clouds begin to

emerge in the west. We begin to get nervous. A single nothing of a cloud like

this, at the right time and at the right place, and we are done. We carefully

study the line of their movement and develop desperate scenarios of the type:

... immediately before the eclipse hop in the car and rush off eastwards. And what

about the Danube river? There's no bridge. OK, then westwards. Why westwards?

There are more clouds there. All right then ... we stay here.

The partial eclipse begins and none of us

is interested. From time to time we do check

whether the Moon encroaches on the Sun's disk in the prescribed

manner but we are much more busy studying the sky, what the clouds are doing.

About midway into the partial eclipse I begin to load the cameras. I am as

nervous as it is possible to be. So are the cameras. Minolta X-700, after

switching off the automatics, refuses fixed exposure times, and simply behaves

confused. This is a critical fault. (Later at home I discovered the camera was

OK, it was me who was confused.) I pick up the standby Soligor camera and load

it with Fujicolor Superia 800. I will take

photographs of the Sun and its immediate surroundings, i.e. the prominences and

the inner and middle corona, using the

MTO 10.5/1100mm mirror lens. Damn it,

the camera is completely dead. It must be the batteries. I hastily replace the

batteries and the camera responds as expected. I load two more cameras with

Agfacolor HDC 400 Plus. The first one goes into the hands of my older daughter

Hana (14 years old). Her task is to photograph the outer corona which falls

outside the field of view of my giant mirror lens. She will use a Sonnar

2.8/200mm fast lens screwed onto a good old Praktica. The second one will be

given to my younger daughter Zdena (11 years old) who will photograph the whole

sky from the Sun to the horizon. That is why she has Minolta X-700 with the

2.8/28mm lens.

About 20 minutes before the total eclipse the sky is nice and clear with the

exception of one cloud which is speeding directly towards the Sun. Our

nerves are strung out like strings. Then a miracle happens. The cloud changes

direction and floats away unbelievably almost perpendicular to the direction

from which it arrived, away from the Sun. The cooling of the ground in the

shadow area changed the air flow which behaved in a different manner than usual.

I mount a filter made from a large computer floppy on my mirror lens and try

to point the camera at the Sun. Another nervous breakdown! I cannot find the

Sun. At night, when I use this lens to photograph the Moon it is very easy to

find. I aim the lens at the Moon as if it was a gun's barrel. The lens even has

protrusions resembling a gun's front sight to help one's aim. However, when the

blinding Sun, into which it is impossible to look directly, is shining into my

eyes, aiming is reduced to mere fumbling about. Fortunately, even the

fumbling was finally successful. Now I must keep it pointed at the Sun. It is

about minus five, maybe minus three, minutes to the total eclipse. Now it is

quite certain that we are going to make it. The narrow crescent that remains

from the solar disk shines from a crystal-clear sky. In the west we can clearly

see the approaching Moon's shadow.

It is quickly getting dark and significantly cooler (by about 5 degrees

compared to the temperature before the partial eclipse began). It is

12 hours 50 minutes.

I remove the filter from the lens. Looking into the last of the bright Sun rays

can do me no harm. I precisely focus the lens and try to be perfectly

concentrated. The moment I have been waiting for such a long time has

arrived and I must not mess it up. All of a sudden, without any warning,

the Sun's brightness abruptly fades away and at the rim of the solar disk, which

just a couple of seconds back blinded my eyes, there shines only a sparkling

strip of light justifiably called the

diamond ring.

Its shine quickly dies down and breaks into little bright stars

- Bailey's beads. These are caused by the

irregularities of the Moon's surface. While most of the gleaming solar disk is

already covered the last sunrays still manage to come through at some places.

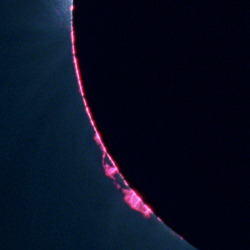

What a magnificent view. After a few seconds even the

last bead disappears

and the solar limb adopts a bright red color which also

quickly fades away. The red color belongs to the

chromosphere,

a thin layer of gas, floating above the visible

solar surface.

The look into the viewfinder of my camera will never be forgotten until the end

of my life. A dark, blue-grey sky, a corona glowing with silver light and

beautiful richly red prominences, floating above

the "black Sun".

The moving of the Moon is clear to see.

After ten to fifteen seconds it is clearly visible how the Moon hides the

prominences on one side of the Sun and unveils them on the opposite side.

The morning of August 10, 1999 found me sitting at my computer pouring over

the recent images from a meteorological

satellite and the weather forecast

downloaded via the Internet from the server of Meteo France. The situation

looked exceptionally bad. The only ray of hope was a small hole

in the cloudy blanket over Hungary, between the Balaton lake and Szeged, visible

in Meteo France's weather forecast. I wanted to check whether other meteorological

institutions were of the same opinion, but they were playing it safe, probably

from fear of risking being blamed by disappointed people, and issued statements

of the "If it does not rain, you will not get wet" variety. There was nothing

left for it but to believe the French. At high noon the final decision was made.

We were going to Hungary, to the vicinity of the town of Paks, which should lie

in between the two cold fronts.

At 14.30 hrs our 8 member strong expedition sets off in two cars from the

Brno observatory. We consistently avoid all motorways, first class state roads

and main border crossings. We are scared of becoming stuck in the predicted

traffic jams. As we are crossing the border from the Czech republic to Austria

in Potorná light drizzle

gradually turns into torrential rain. The falling rain dampened our spirits in

direct proportion to the amount of water falling from the heaven. When we

finally weave our way, at about an hour till midnight, to the Balaton lake the

weather is beginning to improve. We drive around the hopelessly overcrowded

Balaton lake and head farther southeast. At midnight we are almost there. Just

a couple of kilometres from the centre of the totality belt we stop in a woods

where we are going to rough it until the morning. When we lie down on our

carimats, attended by hosts of mosquitoes, we have above us the canopy of the

sky with "millions" of stars and we are overwhelmed by the view of the Milky Way.

The mood is on the rise.

The buzzing of mosquitoes is not the best of lullabies, especially if you

have blood group B. I don't know why the beasts are not attracted by group O.

However, in the end fatigue takes over. The next thing I know I start awake as

light flashes and distant thunder sounds overhead. Before my sleepy head

registers what's going on heavy drops of water fall on the sleeping bag.

Goddamit, the cold front has arrived! But is this the first one or the second

one or ... I wish I could get online on the Internet and download a recent image

from the satellite. We have to seek shelter in the car and catch some sleep

sitting inside and waiting till the morning. Low spirits reach new depths.

However, after eight in the morning a strip of blue sky appears in the west and

extends, slowly but definitely towards us. The front has gone and everyone

cheers up.

Morning lethargy quickly disappears as we get into the cars and drive the

remaining few kilometres to our target looking for a spot suitable for

observation. We find it on the edge of a typical Hungarian field of maize about

2km SSE from the village of Németkér. It is

almost at the centre line of the strip of totality, less than ten kilometres

away from the town of Paks. The weather

looks splendid. The sky is clear with the final traces of the disappearing

front discernible at the distance in the east. How I wish the eclipse happened now!

But right now, the total eclipse is almost minus three hours away. About an hour

later small, under normal circumstances beautiful, cumulus clouds begin to

emerge in the west. We begin to get nervous. A single nothing of a cloud like

this, at the right time and at the right place, and we are done. We carefully

study the line of their movement and develop desperate scenarios of the type:

... immediately before the eclipse hop in the car and rush off eastwards. And what

about the Danube river? There's no bridge. OK, then westwards. Why westwards?

There are more clouds there. All right then ... we stay here.

The partial eclipse begins and none of us

is interested. From time to time we do check

whether the Moon encroaches on the Sun's disk in the prescribed

manner but we are much more busy studying the sky, what the clouds are doing.

About midway into the partial eclipse I begin to load the cameras. I am as

nervous as it is possible to be. So are the cameras. Minolta X-700, after

switching off the automatics, refuses fixed exposure times, and simply behaves

confused. This is a critical fault. (Later at home I discovered the camera was

OK, it was me who was confused.) I pick up the standby Soligor camera and load

it with Fujicolor Superia 800. I will take

photographs of the Sun and its immediate surroundings, i.e. the prominences and

the inner and middle corona, using the

MTO 10.5/1100mm mirror lens. Damn it,

the camera is completely dead. It must be the batteries. I hastily replace the

batteries and the camera responds as expected. I load two more cameras with

Agfacolor HDC 400 Plus. The first one goes into the hands of my older daughter

Hana (14 years old). Her task is to photograph the outer corona which falls

outside the field of view of my giant mirror lens. She will use a Sonnar

2.8/200mm fast lens screwed onto a good old Praktica. The second one will be

given to my younger daughter Zdena (11 years old) who will photograph the whole

sky from the Sun to the horizon. That is why she has Minolta X-700 with the

2.8/28mm lens.

About 20 minutes before the total eclipse the sky is nice and clear with the

exception of one cloud which is speeding directly towards the Sun. Our

nerves are strung out like strings. Then a miracle happens. The cloud changes

direction and floats away unbelievably almost perpendicular to the direction

from which it arrived, away from the Sun. The cooling of the ground in the

shadow area changed the air flow which behaved in a different manner than usual.

I mount a filter made from a large computer floppy on my mirror lens and try

to point the camera at the Sun. Another nervous breakdown! I cannot find the

Sun. At night, when I use this lens to photograph the Moon it is very easy to

find. I aim the lens at the Moon as if it was a gun's barrel. The lens even has

protrusions resembling a gun's front sight to help one's aim. However, when the

blinding Sun, into which it is impossible to look directly, is shining into my

eyes, aiming is reduced to mere fumbling about. Fortunately, even the

fumbling was finally successful. Now I must keep it pointed at the Sun. It is

about minus five, maybe minus three, minutes to the total eclipse. Now it is

quite certain that we are going to make it. The narrow crescent that remains

from the solar disk shines from a crystal-clear sky. In the west we can clearly

see the approaching Moon's shadow.

It is quickly getting dark and significantly cooler (by about 5 degrees

compared to the temperature before the partial eclipse began). It is

12 hours 50 minutes.

I remove the filter from the lens. Looking into the last of the bright Sun rays

can do me no harm. I precisely focus the lens and try to be perfectly

concentrated. The moment I have been waiting for such a long time has

arrived and I must not mess it up. All of a sudden, without any warning,

the Sun's brightness abruptly fades away and at the rim of the solar disk, which

just a couple of seconds back blinded my eyes, there shines only a sparkling

strip of light justifiably called the

diamond ring.

Its shine quickly dies down and breaks into little bright stars

- Bailey's beads. These are caused by the

irregularities of the Moon's surface. While most of the gleaming solar disk is

already covered the last sunrays still manage to come through at some places.

What a magnificent view. After a few seconds even the

last bead disappears

and the solar limb adopts a bright red color which also

quickly fades away. The red color belongs to the

chromosphere,

a thin layer of gas, floating above the visible

solar surface.

The look into the viewfinder of my camera will never be forgotten until the end

of my life. A dark, blue-grey sky, a corona glowing with silver light and

beautiful richly red prominences, floating above

the "black Sun".

The moving of the Moon is clear to see.

After ten to fifteen seconds it is clearly visible how the Moon hides the

prominences on one side of the Sun and unveils them on the opposite side.

|

|

|