"Writers, painters, sculptors, architects, passionate lovers of the heretofore intact beauty of Paris, we come to protest with all our strength, with all our indignation, in the name of betrayed French taste, in the name of threatened French art and history, against the erection in the heart of our capital of the useless, and monstrous Eiffel Tower, which the public has scornfully and rightly dubbed the Tower of Babel."

La Protestation des Artistes, including Charles Gounod, Guy de Maupassant, and Alexandre Dumas fils [Quoted in Harriss, p. 20]

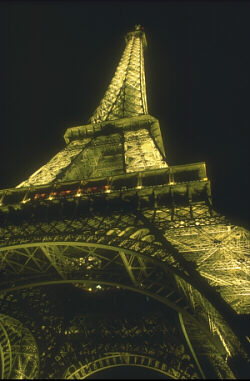

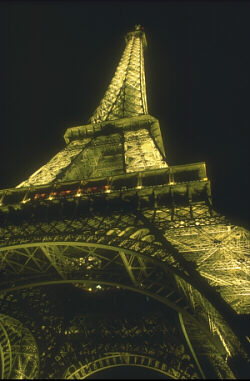

After the resounding success of the Crystal Palace, the focus shifted to France as Paris was the home of a series of great exhibitions. In 1855, the Palais d'Industrie was built and the exhibition brought in 5.1 million visitors from all over the continent. In 1867, 15 million people came. By 1889, the Centennial Exposition with it's Eiffel Tower was a blockbuster event with 32 million attendees. [Harris, p. 7-11]

When it came time for the 1889 Exposition, they wanted to have something for people to remember. The idea of a 1,000 foot tower was something that had been bandied about for years by architects. At the time, the Washington Monument was the largest tower in the world at 555 feet. Edouard Lockroy was the Minister of Commerce and Industry who drew the intial plans for the Centennial Exposition in Paris.

Lockroy published a note in the Journal Officiel and announced that bidding was open for a thousand foot tower. The responses were fairly diverse. One proposal was in the form of a giant guillotine, another was a giant garden sprinkler that could water the city in case of drought.

Eiffel won the competition and was awarded a subsidy of $300,000, putting $1.3 million of his own money on the line. Eiffel got to operate the tower (as well as the restaurants, cafés, and other ways of separating people from their money once they got on the tower) for twenty years, after which ownership reverted to the City of Paris.

By the time all the competing and awarding was done, however, there was just about two years to actually build the tower. The Washington Monument, next highest tower in the world, had taken 36 years. This was an era of great change, and one with no parallels in history. It was the engineers, not the generals or politicians who were leading this revolution, and Eiffel had been at the forefront, helping bridges, railways, and the Statue of Liberty. [Harris, p. 37]

He got the job done, with the loss of only one life. By early 1889, visitors were climbing hundreds of steps to get on the first and second platforms of the towers. The elevators almost didn't make it because French procurement regulations required that the bid by the Otis Elevator Company be rejected the first time. When no French company would bid on the crucial elevator from the first to the second platform. Otis was allowed to rebid and completed the job by mid-June, not long after the opening of the Exposition. [Harris, p. 95]

On June 10, Eiffel held his grand opening, squiring royalty to the top, including tours of his private apartments. In the coming weeks, guests to to the tower included the Shah of Persia, the Prince of Wales, the King of Siam, the Bey of Djibouti, the President of France, Buffalo Bill, and Thomas Edison. Young women purchased special dresses made for the occasion, called the Eiffel ascensionniste." Over 1.9 million people came to the tower during the Exposition. [Harris, p. 122, 230]

The tower left behind a lasting legacy. Today, the Eiffel Tower still gets twice as many visitors as the Louvre. [Barthes, p. 9] The tower was used extensively by Eiffel over the next years as a serious science instrument. Working with the French Central Weather Bureau, Eiffel installed thermometers, barometers, and anemometers. Later, Eiffel's began experimenting with aerodynamics, building the world's first reliable wind tunnel in the tower.

Although Eiffel won the tower competition, there was another serious contendor. Electricity and lighting was the key technology during this period. Edison's carbon filament lamp was first made public at the Paris Electricity Exposition of 1881. Up till then, electric lighting was all arc lighting. [Schivelbusch, p.58]

In the period 1880 to 1920, electricity "permeated modern urban life." The applications of this general purpose infrastructure were astounding: electroshock therapy in medicine; electrocultured galvanised plants in agriculture; local traffic systems; lifts; telephones; radio; the cinema; and, of course, countless household appliances. [Schivelbusch, p.79]

Arc lighting was quite popular in the United States. Detroit had 122 towers lighting 21 square miles. Cities ranging from San Jose to Flint, Michigan all built huge arc lighting towers. A young French electrical engineer named Sébillot toured the United States and was hooked. When the 1889 Exposition committee launched a competition for a "monumental landmark," Sébillot teamed up with the architecht Jules Bourdais. [Schivelbusch, pp. 126-128]

In 1885, the team submitted a proposal for a 360 meter Sun Tower. Designed to light "tout Paris," the tower was one of two that were submitted to the competition. The other was by a bridge designer, Gustave Eiffel. Why did the Sun Tower loose out? It was that "the light would dazzle rather than illuminate," blinding viewers with its glory.

Joseph Harriss, The Tallest Tower: Eiffel & The Belle Epoque Regnery Gateway (Washington, 1975). Fascinating biography of Eiffel with particular focus on the tower and the Exposition.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night, University of California Press (Berkeley, 1988). Highly recommended history of lighting. Also recommended is The Railway Journey, the first volume in Schivelbush's trilogy on the dawn of modern life.